- Lionel Butler

The earnest butler passed from losing to the debutant of Riddick Bowe in 1989 to secure the WBC eliminator with Lennox Lewis in 1995. Finally, he gave up in 2010 with a record of 32-17-1 (25). - Howard Smith

Eight years before getting the WBA belt in 1980, Mike Weaver lost to Smith during his first two professional trips. Howard also fought Earnie Shavers, and its last part was decent 17-2 (10). - Tunney Hunsaker

Six months before losing more than six rounds with Cassius Clay, Hunsaker survived the ninth round with the former contender for the title of the world, Tom McNeley. He will retire in 1962 with an estimated record of 19-15-1 (10). - James Broad

The talented man Greensboro had 2-0 when he knocked out the future of WBA Titlist, James “Bonecrusher” Smith in his debut in 1981. He retired in 1993 in 23-10 (15). - Al Malcolm

Malcolm, who lost to Lennox Lewis in 1989, was a solid professional who could not cross him at the top of the national level. Although he won the Midlands Area Pas, he shortened Gary Mason, Hughroy Currie, Noel Quarless and Michael Murray. - Don Waldham

Troster in the third round with George Foreman in 1969, Waldham managed to pass longer than many future enemies of Slugger in ponderous weight. Waldham, 5-5-2, did not fight again. - Woody Goss

Goss was detained in the round of opening by Joe Frazier in 1965, when he abandoned his future king. He got involved in two fights with a noteworthy difficult, Jacek O’halloran before he left in 1969 with a record of 6-5-2 (3). - Lupe Guerra

The debut opponent of Frank Bruno mixed with a decent company. Guerra, flattened by Substantial Frank in one round in 1982, also fought (and was hit by) Leon Spinks, Tony Tucker and Jerry Quarry. - Rodell Dupree

After staying four rounds with Larry Holmes in 1973, Dupree was detained by some fighters who would unsuccessfully challenge Larry when he was a champion, like Renaldo Snipes and Randall “Tex” Cobb. - Hector Mercedes

Mercedes was not much better after he was steam by youthful Mike Tyson in 1985. The only other significant name on his album 1-10 is Paul Poirier, who stopped the Mercedes in two parts.

Boxing History

When Muhammad Ali lit the Olympic flame

Published

2 months agoon

Shortly before the Olympic Games in Atlanta in 1996, I was on the phone with Muhammad Ali.

“Will you go to the Olympic Games?” I asked.

“I can’t tell anyone,” Ali answered. “It’s a great secret.”

From this I thought that Muhammad was actually going to Atlanta and most likely lit the Olympic Kauldron.

The boiler lighting is the most essential event of the opening ceremony at every Olympics. The torch is illuminated in Olympia, Greece. The flame is transported in the relay to the country hosting the upcoming games. The journey ends at the main stadium in games where the boiler is fiery and burns until the fire expired during the closing ceremony.

Traditionally, someone from the host country ignites the boiler. At the 1984 Olympic Games Decathlete Johnson Rafer ” In 1992, in Barcelona, a Spanish archer shot a Caldron arrow, waking up the flame.

Ali was an ideal choice for the lighting of the Olympic Kauldron in Atlanta. At the age of eighteen, fighting under the name Cassius Clay, he won a gold medal in Rome. Then he achieved glorious highlands as a boxer and traveled the globe, spreading joy and much more. Atlanta was particularly essential to him. There, after three years of exile from boxing, he returned to the ring to defeat Jerry Quarry. He supplemented the Olympic spirit and was probably the most essential citizen of the world.

But the organizational committee in Atlanta wanted Evander Holyfield (resident of Atlanta) to be the last carrier of the torch. The NBC sports president took Dick Ebersol (whose network was television matches) five months to convince local Olympic officials that Ali should be honor.

The identity of the final torch carrier was a closely guarded secret. The moment of consideration took place on July 19, 1996.

Discus Thrower Al Oerter (former US gold medalist) wore a torch with a flame at the last stage of the trip to the stadium. Holyfield flame passed, who moved the torch through the maze of tunnels to the track, to which the winner of the gold medal of Voula Patoulidou from Greece joined. Holdfield and Patoulidou circled the track and handed over the flame “Od to Joy”.

Evans took the torch towards California. Ali, his own torch in hand, appeared.

Tens of thousands of people began to chant: “Ali! Ali!”

Evans reached out and lit Muhammad’s torch with her own.

Ali was in less than good health at that time. The ignition device designed to rise to the boiler above was ponderous to lightweight when Muhammad touched it. His body was shaking.

Over a billion people around the world look at the flames of the torches, Ali licked his hands and shoulders. But he wouldn’t give up. He did not refuse to release the torch until the work was done. And he won. The flame moved from its torch to the boiler.

It was one of the most memorable Olympic moments in history. No one who noticed that night will forget about it.

For many years I was asked what I consider to be the heritage of Ali, except for its size as a warrior. Each time I point to his example of black pride and his refusal to accept the introduction to the United States Army.

“He became a lighthouse of hope for oppressed people around the world,” I explain. “The experience of being black changed to tens of millions of people because of Ali. Every time he looked in the mirror and said,” I’m so pretty “, he said that black is lovely before becoming fashionable. And when he refused to introduce the United States to the army, he stood in the army around the world, supporting the proposal that unless you have a very good reason to kill people, he is bad. “

But I also started to believe that there is an equally essential element of Ali’s heritage. He was the embodiment of love.

The boiler lighting at the Olympic Games in 1996 was the last main element of the composition for the legend of Ali. Muhammad lived for another twenty years later. But on July 19, 1996, it was a great blessing for the hero’s life.

People who witnessed Ali’s fight in Atlanta were united and look after one man. Hundreds of millions of people around the world, even for a moment, removed all hatred and prejudice from their heart.

Thomas Hauser is the author of Muhammad Ali: His life and times and Muhammad Ali: Hold for the greatest. His e -mail address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. In 2004, the boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the NatLeischer Award for career perfection in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was elected the highest honor of boxing – an introduction to the International Gallery of Fame.

You may like

Boxing History

The first 10 opponents of future heavyweight masters

Published

9 hours agoon

June 14, 2025

Boxing History

Mike Milligan, a man behind the scenes of one of the most colorful eras in British boxing

Published

21 hours agoon

June 14, 2025

Every solemn boxing ephemeral collector has repeatedly seen the name Mike Milligan on British programs and hands in the 1930s to the 1960s. At various times he was a professional boxer, trainer, second, whip and matchmaker. Although his own rings career was miniature and unusual, he was present in other roles for many vast British fights.

Born in London East End in 1908, his Boxing news The obituary states that his real name is Mark Vezan. However, I cannot find a list of this name in official birth or death indexes, so it’s probably wrong. At the age of 15, Milligan joined the Victoria Working Boys boys club in Whitechapel, where the British and European master Harry Mason had his first boxing lessons. At the age of 16, Mike changed his professional, debuting in the notable Premierland, where he won the prince’s sum of 17s 6d (88 pence) for six -handed. He had a few more fights before he turned to the training and made contact with Kingpin Emerging End End Kingpin, Johnny Sharpe. Johnny set Mike for his gym “45” on Mile End Road. Two early Milligan students are Moe Moss and Kid Farlo, both of which he gave Sharpe to manage and became leading professionals. Others Mike trained at 45 gyms, to Jack Hyams, Archie Sexton, Laurie and Sid Raiteri and Billy Mack.

After a few years with Sharpe Milligan, he went to work for Joe Morris, a manager of such stars as Teddy Baldock and Dick Corbett. Mike still worked for Morris in 1934, when Joe, supported by a petite syndicate, bought the lease of an vintage church on Devonshire, Hackney Street, transforming him into a boxing room. The Devonshire club, as it was called, coped with us, prompting Morris and other investors to sell his future promotional Supremo (but then little known) Jacek Solomon. Milligan stopped at Devonshire and worked as an assistant to “home” and Jacek until 1940, when this place was blurred by the Luftwaffe bomb.

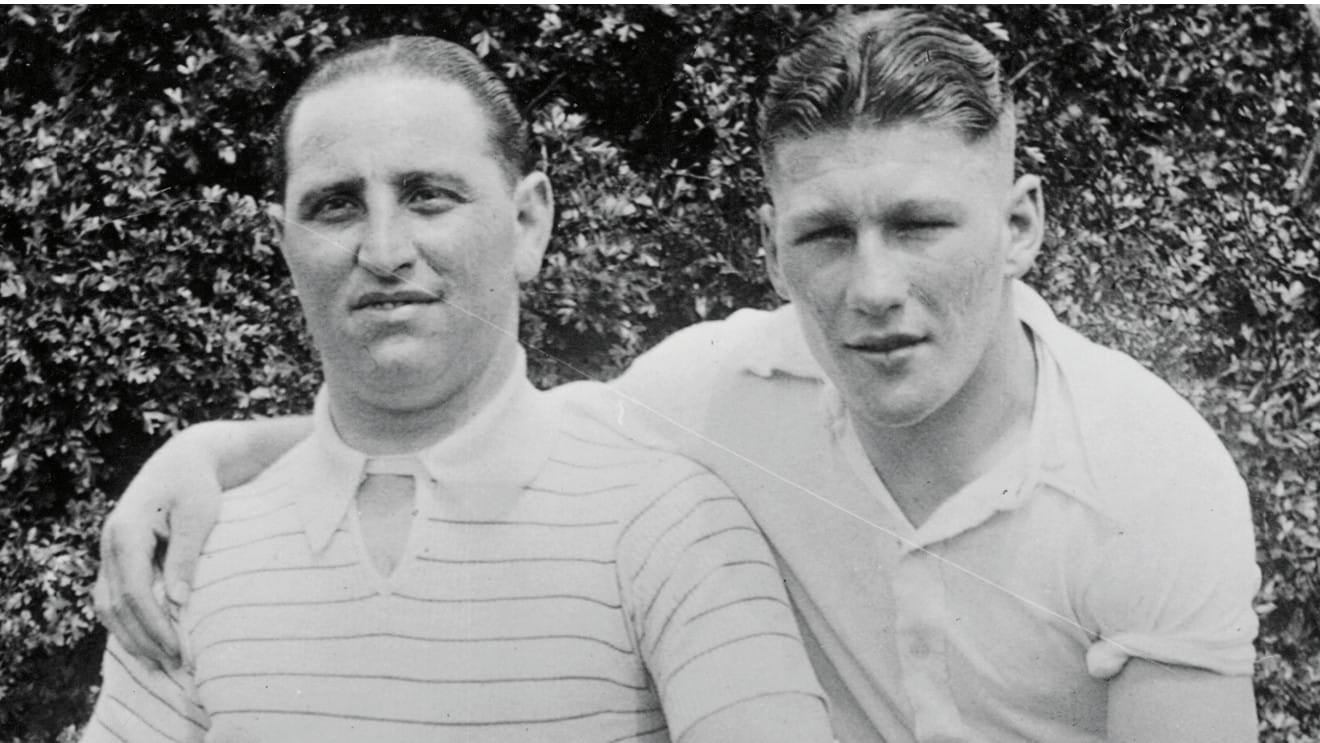

In this miniature time, Devonshire became the leading petite hall of the eastern London. It was during this spell that Mike, who had a gift to detect talent, discovered his greatest discovery of his fists. Milligan took the future British featherlight champion Eric Boon [pictured above right with Milligan] Under his wing after he saw him as a 15-year-old on the account of the Devonshire club. Mike trained Eric and was a key impact in the early years, traveling with him wherever he fought.

In 1940, Milligan joined the army as a shooter in Ra, and also served as an instructor entitled He was annulled from the army after an injury at the site of the weapon and spent six months in the hospital. From there, he returned to work as a whip for Salomons and many other promoters, and became a lasting element of what is on a wonderful pregnancy on the shelf, a place outside, located in a crumbling brick and wavy iron walls. From 1951, Mike worked as a match in places such as Mil End Arena and Epsom Baths, and for many years he was a member of the South Council of the region.

“A lively personality with a pleasant way and enthusiasm for boxing, which radiates positively from him,” was like one newspaper described him in 1940. And this enthusiasm for the game has never decreased. “Mike worked as a bookmaker, but boxing was his life,” noted the obituary in boxes in 1964. “He ate, drank and slept boxing … he rarely left the program, vast or petite.”

The sudden death of Milligan, at the age of 56, shocked the British brotherhood of the fight. Many leading boxing characters – among them Salomons, Sharpe and Benny Huntman – were at his funeral in Rainham in Essex to respect a man who left his marks behind the scenes in one of the most colorful eras of British boxing.

Boxing History

On this day: an everlasted kalambay Sumbay hand Iran Barkley boxing lesson

Published

1 week agoon

June 5, 2025

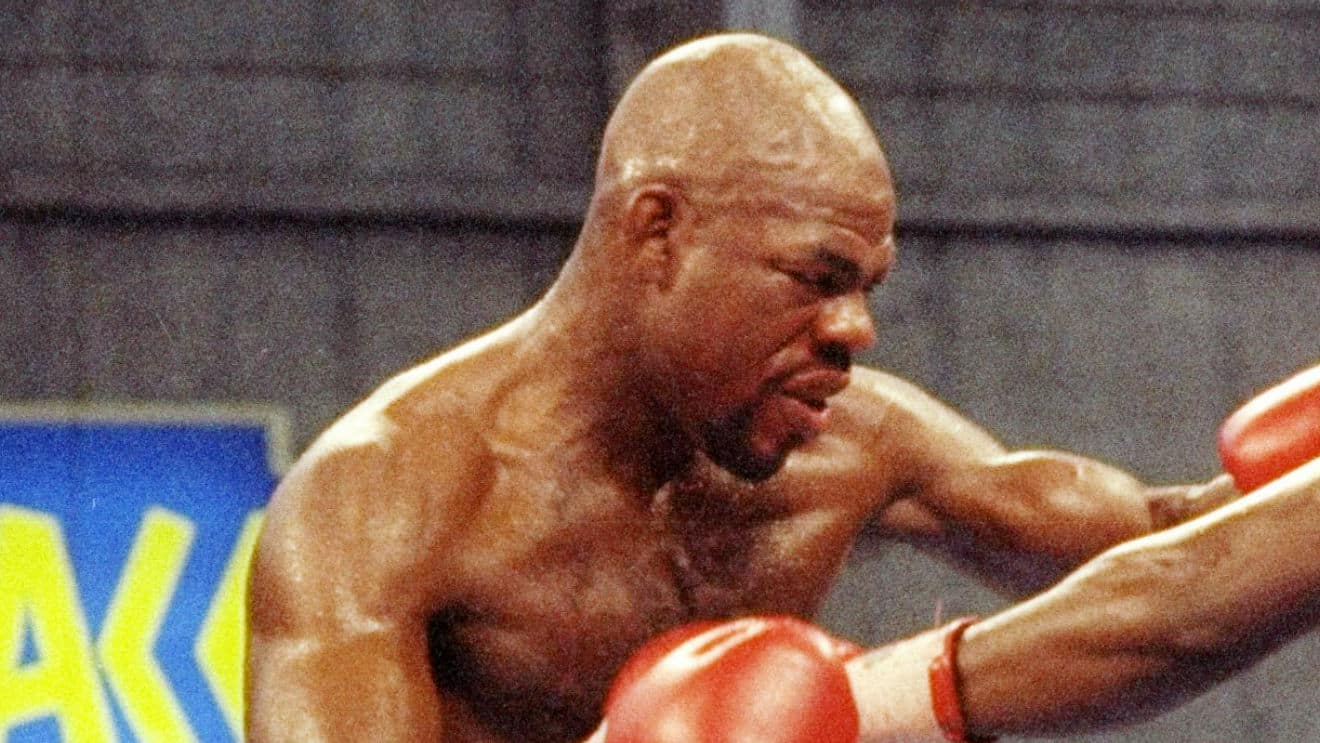

Axis Kalambay at PTS 15 Iran Barkley

Octabar 23 1987; Palazzo dello Sport, Livorno, Italy

Kalambay’s Sumbay is often overlooked when historians call the best medium weights in the era of post-Marvin Hagler. But when someone thinks that Kalambay defeated Herola Graham (twice), Mike McCallum, Steve Collins and Iran Barkley, it is clear that he should not. The Italian silky idol was Muhammad Ali and against the free, gritty and strenuous (and let’s not forget, very good) Barkley, Kalambay showed his extensive repertoire in the last fight for the title WBA Middle Wweight to plan 15 rounds. More educational than exhilarating, Kalambay shows exactly why it was very arduous to beat to raise a free belt.

Do you know? The title of WBA was deprived of Hagler after he signed a contract for the fight with Sugar Ray Leonard instead of a compulsory pretender, Herol Graham. Kalambay upset Graham in the fight for the title of EBU – which was a crazy fight for a “bomber”, in retrospect – to get a shot in a free crown.

Watch out for: The operate of a left stabbaya is arduous to determine. At the end of the fight, Barkley is bruised, bloody and well beaten.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wmmykev8GSE

Hitchins dominates, stops Cambosos to keep the title of IBF

Roy Jones Jr DISSES today’s fighters & Pacquiao APPLAUDS HIM for saying “THEY NOT GIVING ENOUGH”

Boxing results: Olympic gold medalist Andy Cruz stops Hironori Mishiro in round 5, progress in a featherlight eliminator

Trending

-

Opinions & Features4 months ago

Opinions & Features4 months agoPacquiao vs marquez competition: History of violence

-

MMA4 months ago

MMA4 months agoDmitry Menshikov statement in the February fight

-

Results4 months ago

Results4 months agoStephen Fulton Jr. becomes world champion in two weight by means of a decision

-

Results4 months ago

Results4 months agoKeyshawn Davis Ko’s Berinchyk, when Xander Zayas moves to 21-0

-

Video4 months ago

Video4 months agoFrank Warren on Derek Chisora vs Otto Wallin – ‘I THOUGHT OTTO WOULD GIVE DEREK PROBLEMS!’

-

Video4 months ago

Video4 months ago‘DEREK CHISORA RETIRE TONIGHT!’ – Anthony Yarde PLEADS for retirement after WALLIN

-

Results4 months ago

Results4 months agoLive: Catterall vs Barboza results and results card

-

UK Boxing4 months ago

UK Boxing4 months agoGerwyn Price will receive Jake Paul’s answer after he claims he could knock him out with one blow