Boxing History

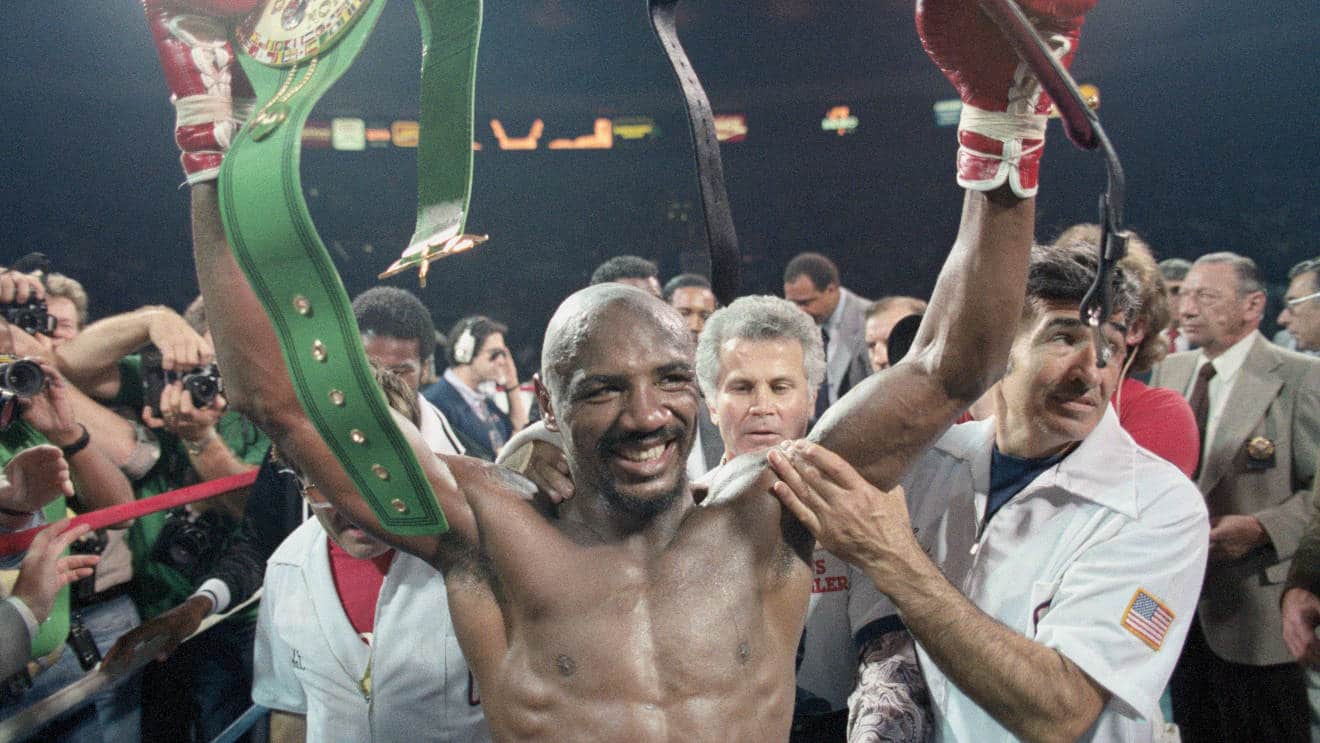

Editor selection: Marvin Hagler – recognition of a boxing legend

Published

3 weeks agoon

The wonderful Marvin Hagler, who was widely respected in the boxing community and was one of the biggest boxing masters, died suddenly on March 13 at the age of 66.

There are usually warning signs against the death of a great warrior. He is aged. Or he is relatively teenage, but in a health failure. The newspapers vacuum their obituaries. The end is close.

There was no such warning here. The message appeared in the post on the official website of the Hagler fan club signed by his wife Kay, who sounded: “I’m sorry I made a very melancholy advertisement. Unfortunately, my beloved husband wonderful Marvin unexpectedly died in your home here in Recent Hampshire. Our family asks you to respect our privacy at this tough time.”

No cause of death was announced. TMZ later informed: “One of the sons of Hagler, James, says TMZ, his father was taken to the hospital in Recent Hampshire earlier on Saturday, March 13 after they experienced trouble breathing and chest pain at home. About four hours later the family was informed that she died.”

Hagler approached his own path. Most fighters do it. He was born in Newark, Recent Jersey, on May 23, 1954. His mother moved his family to the city of Brockton in Brocton, Massachusetts, after the riots in 1967, which destroyed Newark. Marvin began boxing in Brocton and was discovered at the local gym by Goodho and Pat Petronella – brothers who trained him and managed the Ring throughout their career.

Hagler fought with all this career as an average weight. His confession was basic: “Every time, anywhere, in the yard of everyone.” He returned Pro on May 18, 1973 and in fourteen years developed a record 62-3-2 (52). Everyone but the final defect on his ring book was cleaned.

Sugar Ray Seals fought for a disputed draw with Hagler in the family state of Washington Seales. Hagler’s decision about Seales in an earlier fight and destroyed him in one round in a later one.

Bobby Watts won the decision about the family majority over Hagler in Philadelphia and was knocked out in the second round when they met. Also in Philadelphia, a family warrior Willie Monroe Hagler’s decision. They fought twice with Hagler, who struck Monroe in the twelfth and second round.

Vito Antoufermo used what widely recognizes that it was a badly considered draw when he first fought with Hagler. Eighteen months later, Hagler knocked Antoufermo in four rounds.

The only flaw that is not pomsa was the loss of the decision about Sugar Ray Leonard on April 6, 1987 in the final struggle of Hagler’s career. He took the calculated risk against Leonard Hagler. Or more precisely – incorrectly calculated risk. Natural Southpaw, he fought in an orthodox attitude over the first three rounds, shortening the fight for Leonard and losing points on the cards of the results of judges. Lou Filippo scored 115-113 for Hagler. Dave Moretti had it 115-113 for Leonardo. Jose Juan Guerra (who seemed to have a problem with understanding what he watched) threw the decisive Tally 118-110 in favor of Leonard.

Hagler fought the crushing search style and Nestroy. He was as relentless in training as in the ring and wore combat shoes while performing road works. In 1980, in 1980 he took over the throne in the middle weight in the third round of Alan Minter in London and successfully defended his crown against John Mugabami and Roberto Duran. His most significant victory was the knockout of Thomas Hearns in the third round on April 15, 1985, in Non-Stop Slugfest, which is widely considered one of the most invigorating fights in the history of boxing.

After the fight with Leonard Hagler (a month of shame with his 33rd birthday) he left boxing. He moved to Italy, learned the Italian and played the hero in class B action movies. He was a history of success in boxing – a great warrior who retired in good health with money at the bank and remained retired.

One anecdote says size. Flying home from Las Vegas after an eight -digit payment, Hagler called his wife on the phone. Telephones on aircraft were fresh at that time and were activated using a credit card. Marvin talked to his wife for about a minute before he told her: “I have to hang up now. I don’t know how much this thing costs.”

How good was the warrior Hagler?

Six years ago I conducted a survey to argue the largest average importance of the present. Entrepreneurs were restricted to the era after World War II and did not include fighters such as Stanley Ketchel and Harry Greb, because there are not enough film films to assess them properly.

The fighters considered alphabetically are Nino Benvenuti, Gennady Golovkin, Marvin Hagler, Bernard Hopkins, Roy Jones, Jake Lamotta, Carlos Monzon, Sugar Ray Robinson and James Toney. Panels were asked, anticipating the result of each fight whether each of these warriors would fight the other eight in a round-robin tournament.

Twenty -four experts took part in the ranking process. Among them were studied, trainers, warriors, historians and media representatives, from Teddy Atlas and Don Mcrae to Bruce Trampler and Mike Tyson. Voters were to assume that both warriors in each fight were at the point of their careers, when they were able to earn 160 pounds and were able to duplicate their best performance of 160 pounds.

The incomparable Sugar Ray Robinson took first place. Hagler defeated (or one could say that “defeat”) other contenders who end as the second average importance of the present.

In the long run, I once asked Bernard Hopkins how Ray Ryinson dealt with Sugar.

“Sugar Ray Robinson weighing 147 pounds was close to the perfect,” replied Hopkins. “But in medium weight he was defeated. I would fight Ray Robinson and would not give him room to do my things. I would force me to pay a physical price. But in medium weight, I think I would utilize it and win him.”

And how did Hopkins think he would do against Hagler?

“Me and Marvin Hagler were a war,” Bernard replied. “We would both later be in a hospital with straws in our mouths. We would destroy each other. My game plan would be gritty, box, gritty, box. You wouldn’t utilize judges for this fight. You will go through doctors’ reports.”

There was time in Hagler’s career when he decided that he should be presented in the fighting and refer to the media as “the wonderful Marvin Hagler”. But as Muhammad Ali learned after changing his name with Cassius Clay, the world of boxing is not always in line with nomenclature. Finally, after the performance without “wonderful” in one too many fights, Hagler went to court and legally changed his name to the wonderful Marvin Hagler.

Hagler was a real champion in and outside the ring. He deserved the right to call “wonderful”.

Thomas Hauser’s latest book – Gateown: Another year in boxing – He was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the NatLeischer Award for career perfection in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was elected to be introduced to the International Gallery of Sław.

You may like

Boxing History

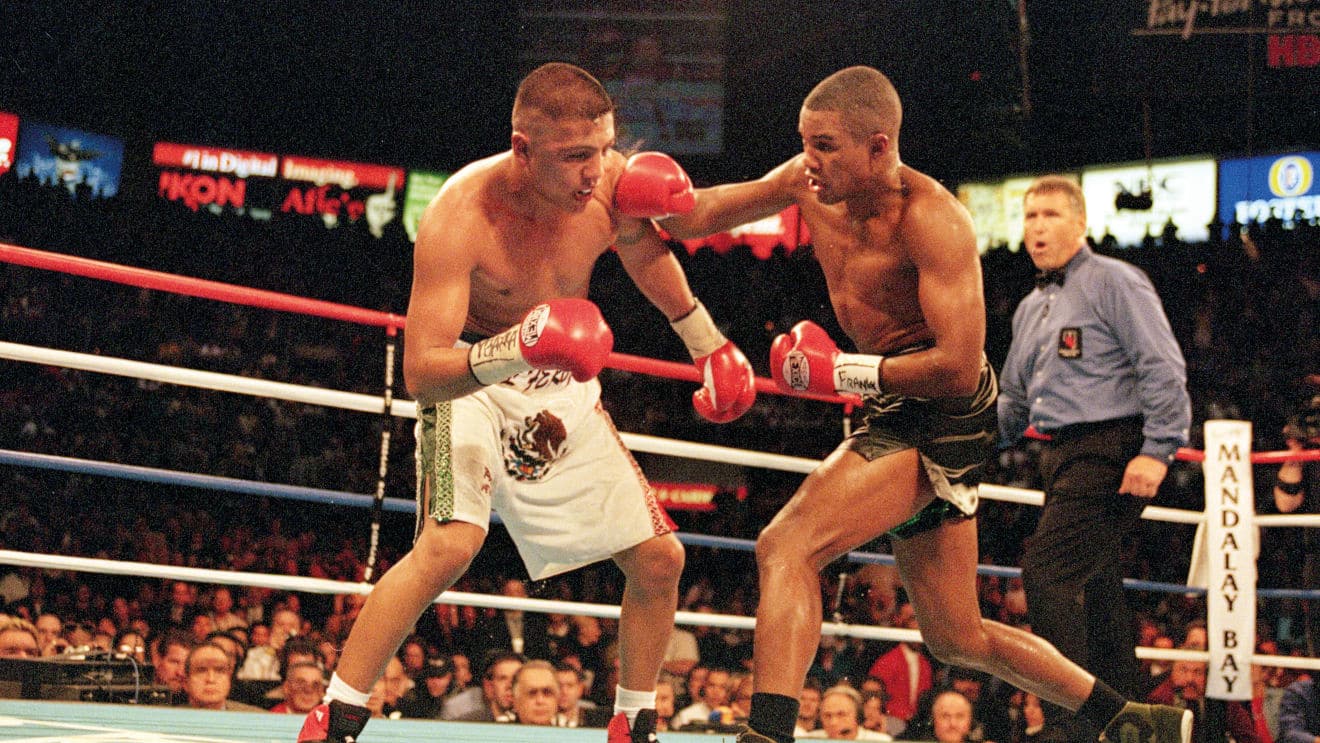

Version – Marco Antonio Barrera wins a furious and electrifying rubber match over Erik Morales

Published

10 hours agoon

May 29, 2025

Marco Antonio Barrera in MD 12 Erik Morales

November 27, 2004; MGM Grand, Las Vegas, NV

Mexican warriors Barrera and Morales ended their epic trilogy in a properly urgent style, creating another unforgettable war. Entering in the start, in the case of the Super Feather WBC Morales belt, the series stood with one winner per item. Morales won the initial meeting in Super-Bantam in 2000, and Barrera secured the creation of a rematch in 2002 in a featherweight-the decisions were questioned. Accordingly, the verdict in the rubber match also caused a debate. As in the previous two meetings, bitter enemies got involved in a furious fight, and the electrifying 11 round turned out to be particularly cruel. Ultimately, Barrera went to the top and adapted Morales’s achievement, becoming the three world letter.

Do you know? At that time, WBO Feather Highland Scott Harrison was interested in an observer in Ringside. He hoped to catch the winner.

Watch out for: In the middle of nine, the fighters are involved in the clinch, and Barrera is bursting morale at the back of the head with a legal apparatus. Uninvited by his opponent, Morales refuses to touch Barrera gloves when the judge was asked.

Boxing History

On this day: Felix Trinidad and Fernando Vargas are sharing, fouls and exhilarating violence

Published

22 hours agoon

May 29, 2025

Felix Trinidad in RSF 12 Fernando Vargas

December 2, 2000; Mandalay Bay, Las Vegas, NV

A lot was expected about the battle of unification of power between Trinidad and Vargas and, fortunately, did not disappoint. Trinidad, who defended his title WBA, jumped out of the blocks and twice started in the opener twice. Vargas returned a favor in the fourth round, sending Trinidad to a mat. Even worse for Felix, he was also deducted to a low blow. The same violation meant that the next point was taken from Trinidad in seventh place, before Vargas lost the point after a closer south of the border in 10. Constant violence with the view lasted to 12., in which the trio knocking up from Trinidad finally ended to a perfectly exhilarating competition.

Do you know? Former victim of Trinidad, Kevin Lueshing, called Boxing news Offices to discuss a brutal conclusion to fight. He said: “It caused a terrible memory of how he finished me.”

Watch out for: The complete HBO Pay-Per-View transmission is available to watch on YouTube. In Undercard he presents himself like Christa Martin, William Joppy and Ricardo Lopez.

This is the latest in the occasional series about the heavyweight champions of the world and their visits to Great Britain. In previous articles I wrote about Primo Carner and Langford himself, and this week I will look at Jacek Johnson and his British concert tour of 1908. Jackjohnson came to Great Britain on Monday, April 27 from the States, when the German steamer, Kronprinz Wilhelm, did in Plymouth. He was accompanied by his manager, Fitzpatrick himself, and two men immediately followed the train from Plymouth to the Paddington station in London, checked in at the Adelphi Hotel, and in the evening he visited the British Botker, in the field of eight circles, to see 20 rounds.

Johnson was in Great Britain to hunt Tommy Burns, also visiting London, to force him to defend the title, which, as we know, took place in Sydney eight months later. Two men exchanged words in Sporting Press and Burns, who stayed in Jacek’s Castle, in a pub in Hampstead, immediately published 1000 pounds from The Sporting Life, stating that if the Johnson camp was fitting to this amount, the fight was turned on. Fitzpatrick opposed the terms for which Burns insisted on the proposed match and refused to cover money. Johnson challenged the shooting moir, but it was rejected when Moir drew a color line and refused to meet the American.

Johnson spent the majority of this summer, appearing in various music rooms in Great Britain, boxing at exhibitions with a wide British heavyweight, including Jewey Smith, Jam Styles and Fred Drummond. In those days it was quite lucrative for the highest level boxers. Then he was tailored to Ben Taylor (Woolwich) to a 20-round competition in Plymouth. Jack trained on a fight at Regent’s Park and at the Junior High School at the National Sporting Club. He left the Waterloo station on July 30 to go to Plymouth for a fight, which was to take place the next day in Cosmopolitan Gymnasium, Mill Street. A vast contingent of fans welcomed him in the city of Devon, which at that time was the center of the fight of the great importance.

The competition, as you can expect, turned out to be one -sided when Johnson defeated Taylor with ease, raising him 11 times in front of a judge called Halt in the eighth round. After the duel, Johnson praised Taylor at his break, stating that he never met a player during his entire career. Later that night at the Mount Pleasant Hotel gathered at the Mount Pleasant Hotel, near the cosmopolitan, where Taylor founded his training camp, and Jack appeared to give Taylor again congratulations to Taylor for organizing such a good competition.

Johnson took part in a series of exhibitions in Dublin, and then in Bristol, where he participated in the Bristol City Vs Everton football match in Ashton Gate – his first experience in sport. Until September 7, he returned to London and announced that in October he was adapted to Box Mike Schreck at the National Sporting Club. On September 14, Schreck manager Jimmy Kelly was announced that the fight was not turned off because Schreck could not be relied to get to a decent condition for the fight.

Together with Burns in Australia, Johnson remained high and desiccated, without a significant fight, so the National Sports Club organized a competition against Sam Langford, which took place at the club on November 9. What would be a coup d’état – a match between the two best bulky scales in the world – but unfortunately this did not happen. On Monday, September 21, Johnson left the Charing Cross Station on the planned Łódź train at 13.20 to France to start a long journey to Australia, where he finally met and defeated Tommy Burns three months later.

Hitchins calls Haney for showdown

HEATED! Jake Paul vs Julio Cesar Chavez Jr – AUIDENCE Q&A – DAZN Boxing

Ekow Essuman Reflects On Josh Taylor Win & Wants Conor Benn

Trending

-

Opinions & Features3 months ago

Opinions & Features3 months agoPacquiao vs marquez competition: History of violence

-

MMA3 months ago

MMA3 months agoDmitry Menshikov statement in the February fight

-

Results3 months ago

Results3 months agoStephen Fulton Jr. becomes world champion in two weight by means of a decision

-

Results3 months ago

Results3 months agoKeyshawn Davis Ko’s Berinchyk, when Xander Zayas moves to 21-0

-

Video3 months ago

Video3 months agoFrank Warren on Derek Chisora vs Otto Wallin – ‘I THOUGHT OTTO WOULD GIVE DEREK PROBLEMS!’

-

Video3 months ago

Video3 months ago‘DEREK CHISORA RETIRE TONIGHT!’ – Anthony Yarde PLEADS for retirement after WALLIN

-

Results3 months ago

Results3 months agoLive: Catterall vs Barboza results and results card

-

UK Boxing3 months ago

UK Boxing3 months agoGerwyn Price will receive Jake Paul’s answer after he claims he could knock him out with one blow