Boxing History

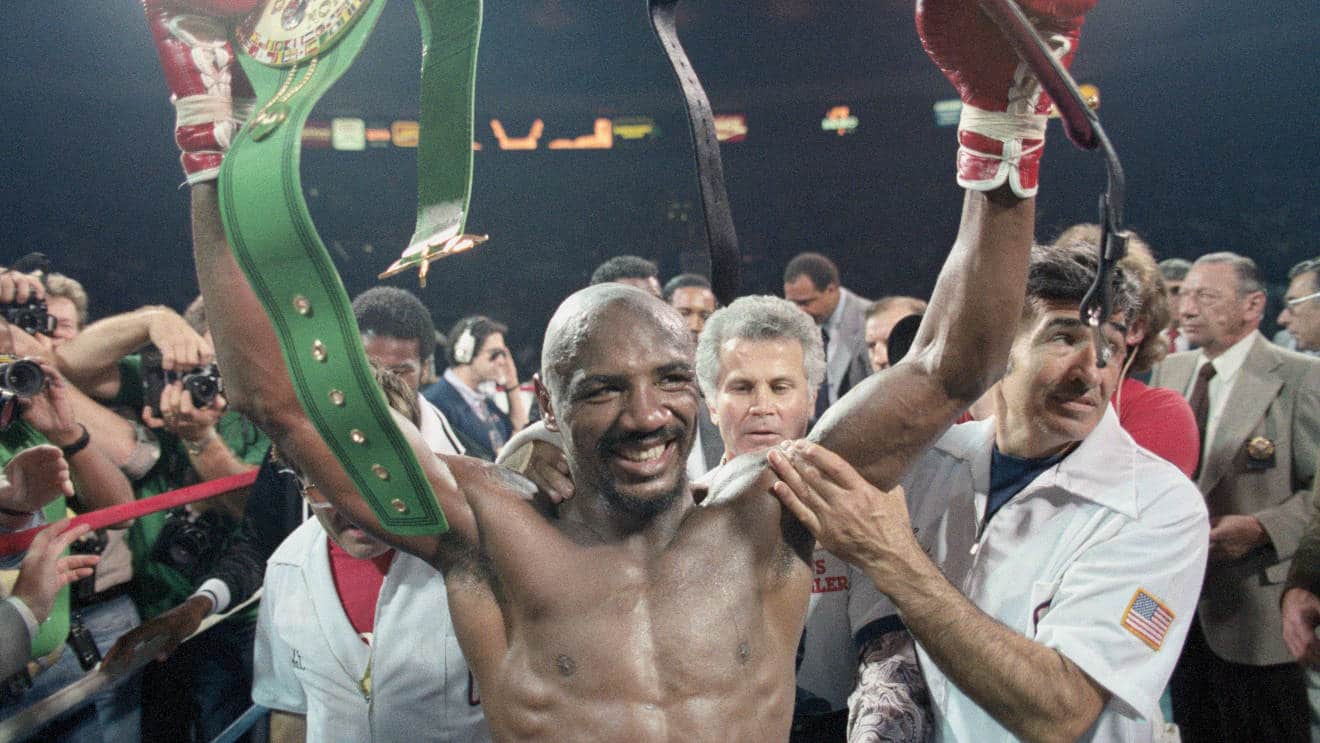

Editor selection: Marvin Hagler – recognition of a boxing legend

Published

10 months agoon

The wonderful Marvin Hagler, who was widely respected in the boxing community and was one of the biggest boxing masters, died suddenly on March 13 at the age of 66.

There are usually warning signs against the death of a great warrior. He is aged. Or he is relatively teenage, but in a health failure. The newspapers vacuum their obituaries. The end is close.

There was no such warning here. The message appeared in the post on the official website of the Hagler fan club signed by his wife Kay, who sounded: “I’m sorry I made a very melancholy advertisement. Unfortunately, my beloved husband wonderful Marvin unexpectedly died in your home here in Recent Hampshire. Our family asks you to respect our privacy at this tough time.”

No cause of death was announced. TMZ later informed: “One of the sons of Hagler, James, says TMZ, his father was taken to the hospital in Recent Hampshire earlier on Saturday, March 13 after they experienced trouble breathing and chest pain at home. About four hours later the family was informed that she died.”

Hagler approached his own path. Most fighters do it. He was born in Newark, Recent Jersey, on May 23, 1954. His mother moved his family to the city of Brockton in Brocton, Massachusetts, after the riots in 1967, which destroyed Newark. Marvin began boxing in Brocton and was discovered at the local gym by Goodho and Pat Petronella – brothers who trained him and managed the Ring throughout their career.

Hagler fought with all this career as an average weight. His confession was basic: “Every time, anywhere, in the yard of everyone.” He returned Pro on May 18, 1973 and in fourteen years developed a record 62-3-2 (52). Everyone but the final defect on his ring book was cleaned.

Sugar Ray Seals fought for a disputed draw with Hagler in the family state of Washington Seales. Hagler’s decision about Seales in an earlier fight and destroyed him in one round in a later one.

Bobby Watts won the decision about the family majority over Hagler in Philadelphia and was knocked out in the second round when they met. Also in Philadelphia, a family warrior Willie Monroe Hagler’s decision. They fought twice with Hagler, who struck Monroe in the twelfth and second round.

Vito Antoufermo used what widely recognizes that it was a badly considered draw when he first fought with Hagler. Eighteen months later, Hagler knocked Antoufermo in four rounds.

The only flaw that is not pomsa was the loss of the decision about Sugar Ray Leonard on April 6, 1987 in the final struggle of Hagler’s career. He took the calculated risk against Leonard Hagler. Or more precisely – incorrectly calculated risk. Natural Southpaw, he fought in an orthodox attitude over the first three rounds, shortening the fight for Leonard and losing points on the cards of the results of judges. Lou Filippo scored 115-113 for Hagler. Dave Moretti had it 115-113 for Leonardo. Jose Juan Guerra (who seemed to have a problem with understanding what he watched) threw the decisive Tally 118-110 in favor of Leonard.

Hagler fought the crushing search style and Nestroy. He was as relentless in training as in the ring and wore combat shoes while performing road works. In 1980, in 1980 he took over the throne in the middle weight in the third round of Alan Minter in London and successfully defended his crown against John Mugabami and Roberto Duran. His most significant victory was the knockout of Thomas Hearns in the third round on April 15, 1985, in Non-Stop Slugfest, which is widely considered one of the most invigorating fights in the history of boxing.

After the fight with Leonard Hagler (a month of shame with his 33rd birthday) he left boxing. He moved to Italy, learned the Italian and played the hero in class B action movies. He was a history of success in boxing – a great warrior who retired in good health with money at the bank and remained retired.

One anecdote says size. Flying home from Las Vegas after an eight -digit payment, Hagler called his wife on the phone. Telephones on aircraft were fresh at that time and were activated using a credit card. Marvin talked to his wife for about a minute before he told her: “I have to hang up now. I don’t know how much this thing costs.”

How good was the warrior Hagler?

Six years ago I conducted a survey to argue the largest average importance of the present. Entrepreneurs were restricted to the era after World War II and did not include fighters such as Stanley Ketchel and Harry Greb, because there are not enough film films to assess them properly.

The fighters considered alphabetically are Nino Benvenuti, Gennady Golovkin, Marvin Hagler, Bernard Hopkins, Roy Jones, Jake Lamotta, Carlos Monzon, Sugar Ray Robinson and James Toney. Panels were asked, anticipating the result of each fight whether each of these warriors would fight the other eight in a round-robin tournament.

Twenty -four experts took part in the ranking process. Among them were studied, trainers, warriors, historians and media representatives, from Teddy Atlas and Don Mcrae to Bruce Trampler and Mike Tyson. Voters were to assume that both warriors in each fight were at the point of their careers, when they were able to earn 160 pounds and were able to duplicate their best performance of 160 pounds.

The incomparable Sugar Ray Robinson took first place. Hagler defeated (or one could say that “defeat”) other contenders who end as the second average importance of the present.

In the long run, I once asked Bernard Hopkins how Ray Ryinson dealt with Sugar.

“Sugar Ray Robinson weighing 147 pounds was close to the perfect,” replied Hopkins. “But in medium weight he was defeated. I would fight Ray Robinson and would not give him room to do my things. I would force me to pay a physical price. But in medium weight, I think I would utilize it and win him.”

And how did Hopkins think he would do against Hagler?

“Me and Marvin Hagler were a war,” Bernard replied. “We would both later be in a hospital with straws in our mouths. We would destroy each other. My game plan would be gritty, box, gritty, box. You wouldn’t utilize judges for this fight. You will go through doctors’ reports.”

There was time in Hagler’s career when he decided that he should be presented in the fighting and refer to the media as “the wonderful Marvin Hagler”. But as Muhammad Ali learned after changing his name with Cassius Clay, the world of boxing is not always in line with nomenclature. Finally, after the performance without “wonderful” in one too many fights, Hagler went to court and legally changed his name to the wonderful Marvin Hagler.

Hagler was a real champion in and outside the ring. He deserved the right to call “wonderful”.

Thomas Hauser’s latest book – Gateown: Another year in boxing – He was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the NatLeischer Award for career perfection in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was elected to be introduced to the International Gallery of Sław.

You may like

Boxing History

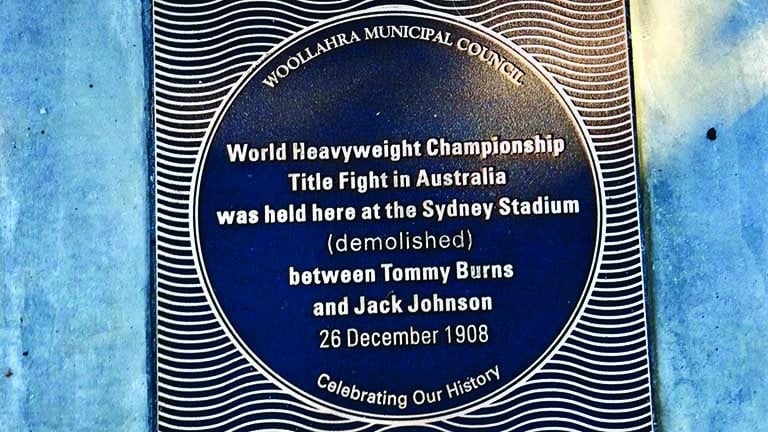

Tommy Burns-Jack Johnson and Harry Mallin honored with plaques

Published

4 months agoon

November 3, 2025

IT says a lot about the social importance of boxing that monuments are being unveiled around the world in honor of the great boxers of the last over 100 years. The latest is a plaque commemorating the world heavyweight title fight between Tommy Burns and Jack Johnson. It stands on a footpath in Rushcutters Bay in Sydney, Australia, near the former Sydney Stadium where the 1908 fight took place.

Johnson chased Burns around the world to get the fight. As a black man in the early 20th century, he fought his greatest battle outside the ring, fighting against widespread racism, making securing a shot at the biggest prize in sports a monumental one.

Jack followed Tommy to London, where the latter engaged in several subtle fights, defeating outclassed Brits Gunner Moir and Jack Palmer. Upon arrival, Johnson visited Arthur “Peggy” Bettinson at the National Sporting Club in Covent Garden, and Peggy offered to arrange a world title fight between him and Burns for a fee of $12,500. Burns, however, found the offer ridiculously low and demanded $30,000 to defend against Johnson.

After destroying Wexford’s Jem Roche in the Dublin round, Tommy went to Paris for a few fights and Jack followed him. After knocking out London’s Jewey Smith and Australia’s Bill Squires in the French capital, Burns was tempted to travel to Australia for a rematch with Squires and a fight with another Australian, Bill Lang.

Australian promoter Hugh D. (“Huge Deal”) McIntosh paid Burns handsomely for these two simple defenses and began collecting the $30,000 Tommy was asking for to fight Johnson. Already funded, McIntosh wrote to Johnson in London and offered him $5,000 to challenge Burns for the world crown in Sydney. Even though Jack didn’t like having to accept one-sixth of what the champion was going to receive, the opportunity was too good to pass up.

They met on Boxing Day 1908 in an open-air stadium originally built for the Burns-Squires fight. Twenty thousand fans sat inside the stadium, while about 30,000 stayed outside, climbing trees or telegraph poles to catch a glimpse of the action. The event wowed the world – it was the first time a black man had fought for the world heavyweight crown – but it turned out to be a complete mismatch. In fact, the 5-foot-10, 167-pound Burns had no chance of beating his infinitely more qualified 6-foot-1, 200-pound opponent.

After a prolonged, one-sided beating, Tommy was saved from further punishment when the police stopped the fight in the 14th round. Johnson was declared the winner and the first black world heavyweight boxing champion. Although initially conceived as a short-lived structure, Sydney’s Rushcutters Bay Stadium was later enlarged and covered. It remained an iconic boxing and entertainment venue until its demolition in 1970.

Ten thousand miles away, another plaque was erected in Pimlico, London, honoring Olympic boxing champion Harry Mallin. It is set at Peel House, where Mallin spent most of his working life as a policeman. Arguably the greatest amateur in British history, Harry left the sport with an undefeated record after over 300 fights. He won Olympic gold medals in 1920 and 1924 and five straight ABA titles (1919-23).

After leaving the ring, Harry remained involved with boxing. He managed the British boxing teams at the 1936 and 1952 Olympics and was a life vice-president of the ABA. He served in the Metropolitan Police for five years above normal retirement age, retiring in 1952 with the rank of sergeant-instructor. The Harry Mallin plaque was exhibited by English Heritage last year, but for some reason it seems to have slipped by unnoticed. It is a worthy addition to the growing list of memorials to British boxing heroes.

Boxing History

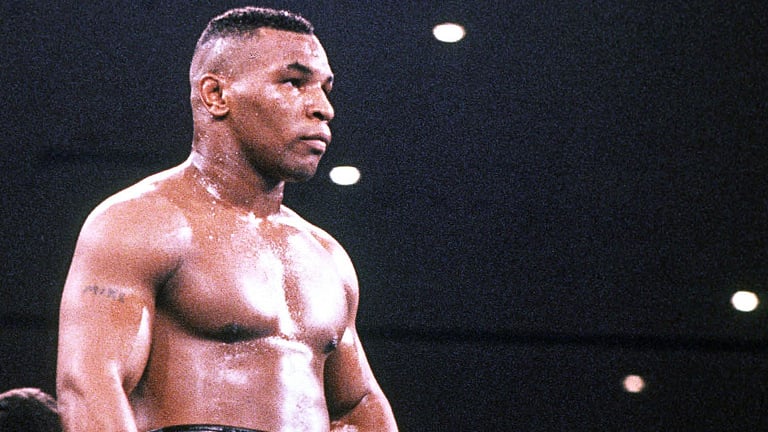

On this day: Mike Tyson knocks out Michael Spinks in the round

Published

4 months agoon

November 2, 2025

These are the most famed 91 seconds in all of boxing, which took place on this day, Monday, June 1988. 31 years ago on this very day, the peak and seemingly unbeatable Mike Tyson faced a man who, in the opinion of a handful of good judges, was the only remaining fighter capable of testing him; maybe even beat him.

The fight, dubbed “Once and For All,” took place at a swanky hotel owned by a certain Donald Trump, The Trump Plaza. Everyone who was anyone was there – Muhammad Ali, Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Sylvester Stallone and Madonna, to name just a handful of the celebrities in attendance – and the fight was the biggest cash-in in sports history at the time. Unfortunately, those who expected a great fight were disappointed.

Two undefeated fighters who had legitimate claims to the heavyweight throne – Tyson won the WBC/WBA and IBF belts, and Spinks won the lineal title after angering Larry Holmes in 1985 – finally faced each other. Tyson, who was only 21 years ancient (he turned 22 three days after the fight), had a record of 34-0 (30), while the 31-year-old Spinks was perfect with a record of 31-0 (21). Despite these adequate qualifications, the fight turned out to be a huge mismatch/anticlimax.

Spinks, a fighter Tyson admired as a teenager while watching him on TV, seemed completely uninterested in the fight as he climbed the ropes in Atlantic City. Much has been written about Spinks’ apparent fear and even fear of what was about to happen to him. He froze and Tyson sensed that his secretiveness had reached another of his victims. Tyson, who had many distractions outside the ring – chief among them the mess of his marriage to Robin Gives – didn’t let any of them bother him; in fact, he used chaos as additional fuel for his fire. He really wanted to hurt Spinks, and everyone has probably read the story about how Tyson, quite literally, was punching holes in his dressing room wall when Spinks’ manager, Butch Lewis, came in to check his gloves before the fight could start.

The fight was over in the blink of an eye. Tyson was smoking when he left the house and after just a minute he sent his fighter a nasty body shot; Spinks is forced to kneel on the ropes. When he rose, the former delicate heavyweight king, who had made history by becoming the first delicate heavyweight ruler to climb to the top and win heavyweight gold, was free from his misery. A sizzling left-right combination to the head knocked Spinks down, almost through the ropes and out of the ring. Spinks tried to get up but was completely gone and was taken down in just 91 seconds.

Tyson barely celebrated, even though millions of his fans did. Spinks later claimed that he “came to fight like I said” but had absolutely nothing to bother Tyson with. As it turned out, this was Tyson’s last truly great performance. He peaked at the age of almost 22, and although he held the undisputed heavyweight title for almost two years, his skills were very slowly eroded; finally to the point where a huge outsider in James Douglas was able to knock him out in 1990.

But that night against Spinks, Tyson’s defeat seemed almost impossible. Tyson had achieved everything he set out to do when he turned professional less than three and a half years earlier.

Boxing History

Ken Buchanan is the greatest British boxer of all time

Published

4 months agoon

November 2, 2025

AFTER my successful blogs informing you about the greatest warrior of all time, this week it’s the turn of the greatest British warrior of all time. I believe that man is Scottish legend Ken Buchanan.

As I said last week, it’s not about yesterday’s players beating today’s players or vice versa, it’s about what they did in their era against the best that were around, and Ken – I think – outshined them all.

I considered many great fighters, including John Conteh, Randolph Turpin, Ted Kid Lewis, Jack Kid Berg, Carl Froch, Joe Calzaghe, Howard Winstone, Jimmy Wilde and even Lennox Lewis, but none matched Buchanan as my all-time greatest British fighter.

I had the pleasure of fighting on the same list as Ken in 1969 (I say fight, my opponent was fighting, I was just practicing shooting). Ken was 23-0 when he fought for the British Lightweight title against Maurice Cullen. Buchanan won by knockout in the 11th round at the National Sporting Club in Mayfair in front of an all-male audience who were only allowed to cheer during the break between rounds.

He continued to defeat world-renowned fighters such as Angel Garcia, but tasted his first defeat when he lost a 15-round decision in Madrid to Miguel Velazquez, who went on to win the welterweight world title. He defeated Velasquez in a rematch, defeated Chris Fernandez and defended his British title against Brian Hudson.

That year he traveled again, this time to Puerto Rico, to challenge legendary Panamanian Ismael Laguna for the WBA lightweight title, whom he defeated by decision over 15 rounds in scorching heat. The WBA was not recognized by the British Boxing Board of Control at the time and he was unable to defend his title at home. Meanwhile, after 10 rounds at Madison Square Garden, he had determined that Denato Paduano would be ranked number one in the world, and in February the following year he defeated Rubén Navarro in Los Angeles for the WBC title, became the undisputed lightweight champion of the world, and was then allowed to defend in Great Britain. There, he knocked out Carlos Hernandez, the former welterweight world champion, before returning to Madison Square Garden for another unanimous decision over Ismael Laguna. Two fights (and wins) later, he returned to Novel York to defend his title against undefeated Roberto Duran. The legendary Panamanian won after a controversial hit and stop, but he always cited Buchanan as his toughest opponent – praise indeed.

The Scot has fought against the best in the world in places such as Puerto Rico, Panama, South Africa, Japan, Canada, Los Angeles and across Europe, fighting on five different continents. He fought at Madison Square Garden five times and won once, with Muhammad Ali as his main supporter. He was voted the best European fighter to ever fight in the USA. He was the only British fighter to ever win the American Boxing Writers’ Fighter of the Year, defeating the likes of Ali and Frazier that year. He was also inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, voted BBC Sports Personality of the Year and awarded an MBE by Her Majesty The Queen.

Here’s to it!

Jai Opetaia joined Zuffa for Chase Undisputed – now titleless

Tim Bradley Predicts Devin Haney vs Rolando Romero Knockout: ‘I Can See It’

IBF withdraws sanction for Opetaia-Glanton after Zuffa announces title defense

Trending

-

Opinions & Features1 year ago

Opinions & Features1 year agoPacquiao vs marquez competition: History of violence

-

MMA1 year ago

MMA1 year agoDmitry Menshikov statement in the February fight

-

Results1 year ago

Results1 year agoStephen Fulton Jr. becomes world champion in two weight by means of a decision

-

Results1 year ago

Results1 year agoKeyshawn Davis Ko’s Berinchyk, when Xander Zayas moves to 21-0

-

Video1 year ago

Video1 year agoFrank Warren on Derek Chisora vs Otto Wallin – ‘I THOUGHT OTTO WOULD GIVE DEREK PROBLEMS!’

-

Analysis11 months ago

Analysis11 months agoRobert Garcia discusses the debate on the greatest Mexican warrior in history

-

Video1 year ago

Video1 year ago‘DEREK CHISORA RETIRE TONIGHT!’ – Anthony Yarde PLEADS for retirement after WALLIN

-

Results1 year ago

Results1 year agoLive: Catterall vs Barboza results and results card