Boxing History

Documentary: Timeline of the heavyweight boxing divisions of the 1950s

Published

3 weeks agoon

It’s on us. The beginning of the newfangled heavyweight division enters the scene. The last decade of the “Black and White Era” has arrived, dating back to the rise and reign of John L. Sullivan in the 1880s. As you can imagine (and probably know), the Black and White era is filled to the brim with landmarks, classic wars, and the overall expansion of boxing traditions. That being said, the 1950s heavyweight division has the tough task of (unwittingly) bringing an end to the “Black and White Era.”

Enter the BIG 4! The 1940s saw the end of the Joe Louis era with his duology against Jersey Joe Walcott. Ezzard Charles and Rocky Marciano eventually joined this rivalry, which extended into the coming 1950s. Speaking of Charles, he defeated Walcott to become champion after Louis retired and entered the 1950s as the face of the division. Despite this, Charles (and, by extension, Walcott) failed to win the hearts of the boxing public as an American Hero [Louis] I had it before. Captain America was an ambassador who could not be imitated, a true “people’s champion.”

So the stage is set for this “last dance.” We have a tight list of top players, an unfavored champion and a changing era of the sport. Things are NOT looking good… but just when you think it’s over, the fat lady won’t sing that note! The Brockton Blockbuster brought excitement and order back to the boxing division, lifting the shadows of Jersey Joe Walcott and Ezzard Charles along the way. What made things even more engaging was the fact that Joe Louis threw his hat back into the mix (we all know that even the best legends can’t resist that comeback). I almost feel guilty for spoiling it, but then again you’ve probably already seen coverage of the BIG 4 in my previous article and video. I’m resting.

What about the era change I mentioned? It came to fruition in 1956, which caused mixed feelings. The surprise was that the division’s elevation was met with a polarizing second half of the decade. The title scene, the contenders, and even the overall state of the division will take a drastic turn and will no longer be what it used to be. Do you know how you can get ailing when the weather changes from balmy to chilly during the day? This is our division from the inside. You’ll see what I mean.

The Olympic Games, as usual, are covered by insurance. The importance begins, in my opinion, at least here, in the 1950s. I mean professional degrees. For the first time, an amateur Olympian successfully paved his way to professional competition.

You have many (and I mean MANY) classic battles up your sleeve:

Joe Louis vs. Rocky Marciano

Ezzard Charles vs. Jersey Joe Walcott III

Jersey Joe Walcott vs. Rocky Marciano I

Rocky Marciano vs. Ezzard Charles II

Floyd Patterson vs. Ingemar Johansson I fight

and much more…

Welcome to the finale of the “black and white era” as we fully transition into the newfangled heavyweight scene that is still ongoing. Your portal to heavyweight boxing knowledge starts here. I wholeheartedly hope you enjoy “A Timeline of the 1950s Heavyweight Boxing Division.” Written, narrated and produced by TheCharlesJackson, author of The Encyclopedia of Boxing.

You may like

Boxing History

Boxing pays tribute to legend John Conteh

Published

14 hours agoon

November 22, 2024

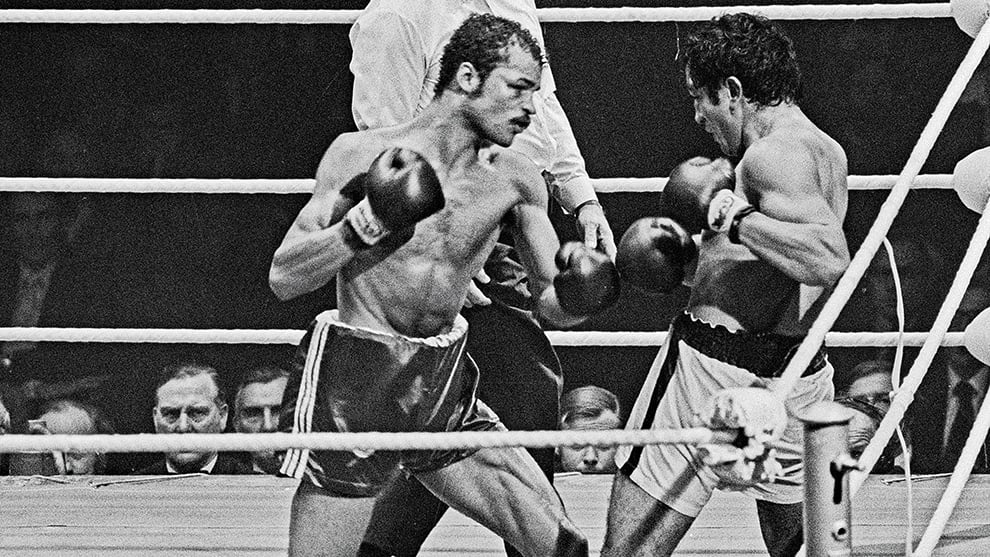

On October 20, London’s Connaught Rooms restaurant hosted a full house for a luncheon in tribute to John Conteh, MBE.

The event was organized by London-based EBA Secretary/Treasurer Ray Caulfield and long-time LEBA benefactor Scott Ewing (John is LEBA Vice-President) to mark the 50th anniversary.vol anniversary of John winning the vacant WBC delicate heavyweight world title after defeating Argentine Jorge Ahumada on October 1, 1974.

But as Scott Ewing said in his opening speech, it was much more about John Conteh the person than the boxer. “John did so much for so many people,” Scott said.

He then described John’s work with Alcoholics Anonymous (“He brought so many back”) and the Variety Club, noting that John was only the second person (besides Jimmy Tarbuck) to be named captain of the Variety Club golf team. “He travels all over the country visiting EBA – he’s a great ambassador,” Scott said, explaining that John was also a major supporter of the Ringside Charitable Trust.

MC John McDonald did a great job all afternoon. He introduced many boxing personalities including world champions Frank Bruno MBE, Steve Collins MBE, Maurice Hope MBE and Colin McMillan BEM. (Bruno received thunderous applause, as did Michael Watson MBE.) There were also stars from other sports, including: Charlie George (football) and Phil Taylor (darts). As you can imagine, LEBA was well represented. I was also delighted to see EBA Croydon chairman Pat Doherty and Brighton stalwart Harry Scott.

Former European and Commonwealth heavyweight champion (and LEBA member) Derek Williams paid tribute to Conteh, describing him as a “true boxing legend”. “Your name has stood the test of time,” Derek said, noting that John had to overcome many challenges and obstacles, and in doing so, he “paved the way for other black warriors.” He said John had “made his mark on boxing” and described him as “boxing royalty”, concluding simply: “Thank you for everything you’ve done.”

We saw a video of John in action – two KOs early in his career, his 12thvol– a round of stoppage of the German Rudiger Schmidtke in the fight for the European delicate heavyweight crown, his two fights with the tardy Chris Finnegan (the first brought John the Briton and Commonwealth titles). And finally, Jorge Ahumada scores those great points.

I was ringside at Wembley that night. As for the BN staff, I was tasked with doing a preview of Conteh-Ahumada and I chose Ahumada, but ended with, “Prove me wrong, John.” And I have never been happier to be proven wrong! John’s brilliant performance really made me feel proud to be British.

A segment of John’s This Is Your Life (a very popular long-running TV show) was also filmed, in which Paul McCartney paid tribute to his fellow Liverpool native, and tributes from boxers who were unable to attend the event were also filmed. These included former world champions Johnny Nelson, Ricky Hatton and Jim Watt – as well as a tribute from boxing writer and broadcaster Adam Smith, who described John as “one of the greatest British fighters produced since [Second World] War.”

British boxer John Conteh during his WBC delicate heavyweight title fight against Argentine Jorge Ahumada at Wembley, October 1, 1974. Conteh won the fight on points and was crowned world champion. (Photo: Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

There was a very successful auction, conducted partly by Ray Caulfield and Scott Ewing and partly by John himself. John has an excellent reputation as an auctioneer at charity events and was in excellent shape. Entertainment was provided by Muhammad Ali Jr, who had everyone laughing with his impressions of his father, and comedian Bobby Davro.

As a nice gesture, John was given his WBC championship belt back – and in a low, modest speech, John thanked everyone for coming. He thanked his family, of which there was a lot – including his wife Veronica (they have been together for 50 years) and children James and Joanne. He also thanked Charles Atkinson, coach at Kirkby ABC, who started John on the path that ultimately led to the world title.

A wonderful tribute to a true boxing legend – and congratulations are in order to Ray Caulfield and Scott Ewing. These events don’t organize themselves

Boxing History

On this day: Lennox Lewis righting the wrong he committed in South Africa by hitting out at Hasim Rahman

Published

5 days agoon

November 17, 2024

Talk about pole work or a knockout when it matters most. Revenge Knockout. On this day in 2001, heavyweight great Lennox Lewis did the job he should have done when he first met Hasim Rahman. Instead, in April this year in South Africa, an ill-prepared (mainly for the altitude) Lewis was run over by a huge right hand from “Rock” Rahman. Rahman’s fifth-round KO victory is now seen as one of the greatest upsets in heavyweight history.

But Lewis, who ended up brawling with Rahman in a TV studio as the second fight approached, had sweet revenge. And it meant so much to Lewis, an avid chess player, that his KO would come sooner than Rahman’s.

They met at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas, and the fight was dubbed “The Final Judgment”. Lewis scored his most satisfying KO of his career.

Lewis, this time fit and piercing, was seven years older at 36 and yet, as it turned out, still close to his best. Rahman (35-2(29)) held the title for seven months and then it was all over. Lewis, 38-2-1(29) entering, lowered the sonic boom in round four.

After inflicting a minor cut above Rahman’s eye in the first round, Lewis also went through the next two rounds. Then, in round four, Lewis landed a brutal left-right combination to the head that sent Rahman’s senses into orbit. Rahman fell, tried to get up, and then fell again. It was the kind of ugly, humiliating knockout defeat that all fighters dread.

Lewis argued with him after the fight, calling Rahman “Has-been Rahman”.

Lewis exacted savage revenge, and while Rahman’s KO was stunning in the first fight, Lewis’ thunderous and thunderous KO made us all almost forget what happened in the first fight. Lewis scored many great knockouts during his ring career, including knockout/stoppage wins over Razor Ruddock, Frank Bruno, Andrew Golota, Shannon Briggs, Michael Grant, Frans Botha and Mike Tyson.

But the ice work Lennox did on that day some 23 years ago is one of his most special.

Boxing History

40 years ago: the “real opportunity” of a ring career began

Published

1 week agoon

November 15, 2024

It may be somewhat ironic that on the day Mike Tyson steps into the ring again, his most demanding rival in the ring turned professional on the same day some 40 years ago. Evander Holyfield, who kicked Tyson’s ass twice (well, once when he was about to repeat the task before Tyson went completely off the hinges and bit his ear off!), was of course part of the famed American Olympic team that conquered in Los Angeles, with other future stars Pernell Whitaker, Meldrick Taylor, Mark Breland and the less fortunate Tyrell Biggs are all professionals on the same card.

It took place at Madison Square Garden four decades ago, and Holyfield, who turned professional as a lithe heavyweight, won a six-round decision over Lionel Byarm. Holyfield was 22 years elderly at the time, and no one – like no one – could have had any idea how great the ring career of “The Real Deal” would be.

Holyfield, disqualified in the second round of the 1984 Olympic semi-finals, had to settle for bronze. Then he filled his trophy cabinet with gold, a whole cart full of gold.

Today, Holyfield is considered the best cruiserweight of all time, and only the great Oleksandr Usyk can claim to be better or as good as him at that weight. Holyfield gave us his first all-time cruiserweight classic in his 15-round war with the great Dwight Muhammad Qawi. Holyfield went through hell to win by split decision, and the fresh champion had to go to hospital to have his body fluids replaced with an IV drip. Holyfield thought long and challenging about quitting the sport because the battle with Qawi was so tough.

But Holyfield was now the world champion, and his team assured him that he would never have to go through such an ordeal again. It’s possible, even considering the wars Holyfield would find himself in at heavyweight, that no one has ever pushed him as challenging or as consistently as Qawi.

After the unification of the cruiserweight division, Holyfield obviously moved up, and there was already talk of a megafight with heavyweight king Mike Tyson. The two sparred for one round and now we know that Evander won. Tyson could intimidate almost everyone he fought, but he was never able to get to Holyfield like that. Holyfield will have to wait a few years before he gets his substantial chance against Tyson.

First came victories over Buster Douglas to become the heavyweight champion, and Holyfield held on for victories over George Foreman (in a monster PPV hit), Bert Cooper (his first date with Tyson postponed) and Larry Holmes. Before Evander had his first epic fight with Riddick Bowe. Holyfield lost to Bowe on points in 12 hotly contested rounds, but his huge heart was never so, well, huge. The rematch came and Holyfield got his revenge. Evander then lost to Michael Moorer and suffered a heart attack during the fight. This was definitely the end.

No, “cured” and armed with a fresh moniker, “Warrior,” Holyfield returned to the top of Ray Mercer, and then came the rubber match with Bowe. After defeating Bowe, Holyfield ran out of gas and was stopped for the first time in his career. This was definitely the end. No, again.

Holyfield scored a victory over Bobby Czyz while looking decidedly ordinary in the process. Then came the fight with Tyson – “Finally.” Tyson was released from prison and regained two pieces of the crown with basic and quick victories over Frank Bruno and Bruce Seldon. Tyson was the overwhelming 25/1 betting favorite at Holyfield, and people around the world were worried about Evander’s health and even his life.

In his most stunning victory, Holyfield defeated Tyson, dropped him, and then stopped him at the end of round 11. Holyfield was now the king of kings. Well, almost. Lennox Lewis would have to be defeated to remove any doubt as to who is the heavyweight king. First came the comeback with Tyson and the infamous “Bite Fight”. Then, with his ear patched, Holyfield took revenge on Moorer by stopping him for eight.

And then came two fights with Lewis, the first fight was called a draw and was considered one of the worst and most controversial decisions in boxing history. In the rematch, Holyfield performed better, but still lost by decision. Amazingly, Evander was able to fight for another 12 years!

The highlight of this period of unnecessary fighting was the victory over John Ruiz, thanks to which Holyfield won the vacant WBA heavyweight belt, making him the only four-weight champion in history. But the good times, good performances and victories began to end. Holyfield lost then drew to Ruiz, lost to Chris Byrd and was stopped by James Toney. However, Holyfield still refused to retire.

Only after defeats to Sultan Ibragimov and Nikolay Valuev (in a fight in which Holyfield was so close to winning, and if it had been, he would have been a five-time heavyweight champion) did Evander finally hang them up with a TKO defeat of Brian Nielsen.

It was one hell of a journey up and down, but most of all up! Holyfield won with a score of 44-10-2(29). Today, after attempting to come back and box on the show circuit while 59-year-old Holyfield was embarrassingly stopped by Vitor Belfort in 2021, Evander will be watching how his elderly rival Mike Tyson fares as he tries to fight on the show again at the age of 58 years.

But what a career Holyfield had. And it started today, 40 years ago.

A Blackpool man is set to contest ‘No. 1 belt in the world”

Jorge Masvidal IMMEDIATELY AFTER BRAWL with Nate Diaz Team; REACTS to Trainer getting JUMPED

Jake Paul could fight Anthony Joshua next if the YouTuber’s stance on the British boxer is clear

Trending

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoMax Holloway is on a mission at UFC 212

-

Interviews1 month ago

Interviews1 month agoCarl Froch predicts that Artur Beterbiev vs Dmitry Bivol

-

Interviews1 month ago

Interviews1 month agoArtur Beterbiev vs Dmitry Bivol

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoCris Cyborg ready to add a UFC title to her collection

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoThe Irish showed up in droves at the Mayweather-McGregor weigh-in

-

Boxing4 months ago

Boxing4 months agoLucas Bahdi ready to test his skills against Ashton Sylve

-

Interviews6 months ago

Interviews6 months agoI fell in love with boxing again

-

Opinions & Features1 month ago

Opinions & Features1 month agoDmitry Bivol: The story so far