Opinions & Features

There’s never a boring moment in the heavyweight division

Published

2 months agoon

It would be difficult to imagine the mess in heavyweight boxing that we left behind so many years ago.

In just two days in January 1998, I wrote two separate but amusing stories in Daily Telegraph (the newspaper used to publish an article every day, which is crazy) which now read like a comedy. They were deadly solemn then.

In the first one I wrote about how Don King had returned to the Recent York courthouse, cornered, in trouble, in danger, and then somehow found a way to freedom. That was Don’s special trick.

In the second article, published the very next day, I wrote about WBO heavyweight champion Herb Hide and his planned fight in June in Las Vegas with Roy Jones. As I said, pure comedy.

King’s compromise was insane, and nothing that was discussed—none of what I wrote—ever happened.

King was in court delayed in 1997, trying to settle a dispute with Frans Botha and his manager, Sterling McPherson. It was the kind of ugliness that ruined almost every heavyweight relationship at the time. King was asked to produce potentially damaging documents, which could have been costly. Instead, the survivalist made a compromise, a deal that would get him out of trouble and out of court. It was always said about King that the moment a contract was signed, negotiations began. He found a rabbit in a hat in a Manhattan courthouse.

King promised Botha a chance to fight Evander Holyfield for the IBF heavyweight title in early August. Botha, it seems, accepted. However, at the same time, King was also negotiating and offering Lennox Lewis and Henry Akinwande the same fight. King kept his options open and juggled like a champ. At the same time, the IBF ordered Holyfield to defend his title against Vaughn Bean. I had to cover this soap opera every day.

“He [King] he called me on Christmas Day,” confirmed Kellie Maloney, Lewis’ manager at the time. Lewis and Maloney chose to ignore the offer and fought Shannon Briggs in Atlantic City in March 1998. The Lewis-Briggs fight is one of the biggest losses in heavyweight boxing. It’s brutal, extraordinary.

Bean’s dilemma was perhaps best summed up by McPherson, who was Frank Warren’s American partner at the time. Warren and King had a spectacular falling out in September 1997. By then, meanness was everywhere, a backdrop to almost every argument that happened.

“I know the only fight Holyfield can take is [to avoid being stripped] Bean’s fight,” McPherson said. “And I also know there’s no hotel or casino in the world that would pay enough money for a fight.” He was absolutely right, and the same stupidity still exists.

The next day the carnival continued and I talked about the Hide-Jones fight in Las Vegas in June. Hide was meeting with Warren to work out a deal; a week later John Fashanu was in Hide’s game and they took an alternate route. As I said, it was the everyday comedy of the heavyweight business.

Jones, I wrote with conviction, had been eyeing Michael Moorer, but Moorer had lost to Holyfield. Jones had turned his attention to Hide. Jones had followed fellow former middleweights Iran Barkley and James Toney into the heavyweight division. Barkley briefly held the magnificent World Boxing Board heavyweight title, and Toney was scheduled to fight Larry Holmes on January 21, less than three weeks after my column.

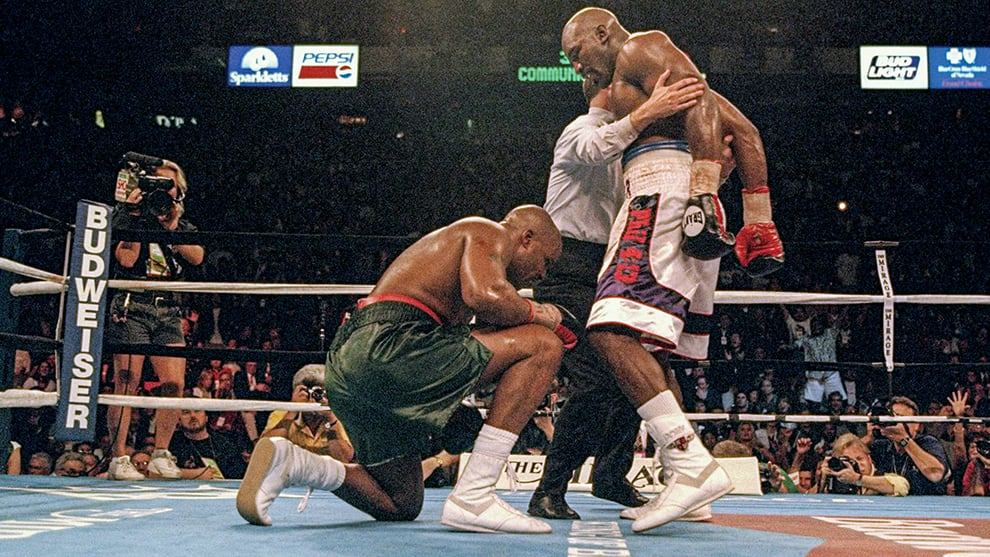

November 8, 1997: Evander Holyfield knocks down Michael Moorer during their fight at the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas, Nevada. Holyfield won the fight by technical knockout. Mandatory Credit: Al Bello /Allsport

All this nonsense was treated as if it were true.

Finally, it happened. And I wrote every crazy detail, twist, turn, blow, and non-event. Some of it is in the modern book

So there was no Holmes and Toney, Akinwande and Holyfield, or Holyfield and Lewis in 1998, but there was Bean against Holyfield. It wasn’t a substantial spectacle. Jones never moved up to heavyweight and fought 12 more times at featherlight heavyweight, and eventually moved up and beat John Ruiz for the WBA heavyweight title in Las Vegas in 2003. That was the same year that Toney, who had never fought in 1998, stopped Holyfield.

Akinwande and Holyfield were close to fighting in the summer of 1998 at Madison Square Garden in front of an estimated 15,000 empty seats. But about 48 hours before the first bell, Akinwande was discovered to have hepatitis B, and the fight was canceled. That was a relief. King, by the way, had been out of Recent York all week—he was somewhere in court fighting the charges. The man is Teflon.

April 10, 2010: Frans Botha arrives at a press conference after their heavyweight fight at the Thomas & Mack Center in Las Vegas, Nevada. Evander Holyfield won the WBF heavyweight title in the eighth round, earning Botha the WBF title. (Photo by Daniel Gluskoter/Icon SMI/Icon Sport Media via Getty Images)

And Botha, who was once at the center of all this turmoil? Well, in 1998 he fought and won twice, and Holyfield was nowhere to be seen. Huge Frans, who was a nice guy, had defeated Stan Johnson and Dave Cherry in a combined 185 seconds in their 1998 fights. Cherry and Johnson had a combined nine wins and 50 losses; in January 1999, Botha was stopped by Mike Tyson in January in Las Vegas. Their fight, riddled with fouls, ended in the fifth round.

In 1999, Lewis and Holyfield met.

It was then and now, well, it’s amusing. Martin Bakole’s emotional homecoming was off the charts, Moses Itaum’s promise and shopping list is amusing, the danger of Daniel Dubois and Anthony Joshua is very real, the Frazer Clarke and Fabio Wardley rematch, Joseph Parker’s experience. And then in December Oleksandr Usyk and Tyson Fury two. Does anyone want to throw Bean, Botha or Barkley in there? Two completely different worlds. Remember, living in history is hazardous. But it’s nice to look back without rose-tinted glasses.

Opinions & Features

Jai Opetaia and the boxing roller coaster

Published

15 hours agoon

November 23, 2024

IT WAS the summer of 2018 when Jai Opetaia and his father-trainer Tapu were returning from boxing after a long day.

The talented Olympian, who had gone 15-0 in the first three years of his professional career, was so broke that he barely had enough gas to get home and wondered whether the sport he had devoted his life to would ever pay off.

As Opetaia remembers that day, she stops. “Fuck, you touched me,” he says, wiping the tears from his eyes and rubbing them on his jogging pants.

“I remember that trip home very vividly. we just didn’t have any coin, we were having a shitty day and we were like, “What the hell does that make sense?” We both talked about quitting boxing and joining the local soccer club.

“We gave boxing everything we had, but we got nothing in return. People don’t know what a rollercoaster I was on. Recalling moments like these from where I am now only shows the fruits of my labor. It makes everything sweeter.”

In the six years since that day, Opetaia has gone 25-0, 19 KOs, and is the current IBF cruiserweight champion and arguably the best 200-pound fighter in the world. On Saturday, he will defend his title for the fourth time in his third fight in a row in Saudi Arabia, where he is the clear favorite of Turki Alalshikh.

Money is not so crucial these days, but the fire inside still burns. There are warriors who wear their hearts on their sleeves, and then there is Opetaia.

“I think I was about 18 before I got my first paycheck,” he says. “Because my fights were so spread out and it was so challenging to get on cards in Australia, I had to invest in myself. C***s have no idea what a fucking journey we’ve been through, man.

“People now see Saudi cards and stuff like that, but they haven’t invested in themselves. They win a few fights and expect high earnings, and that means they miss out on good opportunities. At first, we just wanted opportunities. We went for every possible card. We were losing money on fight cards, we weren’t selling tables, we were in the trenches.

“Whether it was money for sparring or training camps, we didn’t have money for fuel to get to the Sydney sparring session. It was challenging for us, but we found a way and got the cards. It’s been one hell of a journey and that’s why it means so much to me.

Riyad, Saudi Arabia: Jai Opetaia vs. Jack Massey, IBF cruiserweight world title

October 12, 2024

Photo by Mark Robinson Matchroom Boxing.

That victory over Mairis Briedis in July 2022 not only clinched his world title, but also catapulted him to superstardom. However, it was a victory that kept him out of the ring for over a year, as he broke both sides of his jaw at the hands of the Latvian.

“I know I deserve to be here because I went through these challenging times,” he says. “Those frail points and that wasn’t the only one. Eating through a straw for four months was one of them too, those are mind games. I’ve been there and picked myself up off the ground, so now I know what I have to do.

“Even when I broke my arm, I was in a cast for nine months and weighed about 117 kg, I was coming back from the injury. I thought my career was over and that was the fight before Briedis. I went into surgery and was in a cast for nine months and then I got really fat and fat. I drank alcohol and that was it. I was a nobody then, I was a dead nobody.

“I remember my first session, I went to the gym and did two rounds of jumping, punched the bag for two rounds, and then I sat down and just said, ‘My career is over.’ I honestly thought that was it… but 12 months later I beat Briedis. The emotional rollercoaster I’ve been through is fucking crazy.

“And you know what the key is: just show up. That’s all, just show up. Get there. The hardest part is just getting into the gym. The alarm goes off early in the morning and you just think, “What the fuck is going on?” Once you’re in the gym, you’re in business. The hardest thing was to play consistently but achieve absolutely nothing and believe in a goal that was so far away. But now that we’re here, it’s crazy.”

He’s the clear favorite on Saturday night, when 31-year-old Jack Massey tries to turn the cruiserweight division upside down with an unexpected victory. Given the intensity with which Opetaia speaks, it’s tough to imagine him disrespecting anyone, especially considering he now has another mouth to feed on back home. He and his partner welcomed their first child, Lyla Robyn Opetaia, on July 1, marking his first fight as a father.

“It’s a strange set of emotions, but it’s all part of it,” says Opetaia, who left Australia for England in September and will only return after the fight.

“It needs to be done, it adds fuel to the fire, and we are here for a specific purpose. We’re not here to waste time, we have work to do and then I can go home and spend money on my family.

“The birth was a good experience. I cried, I couldn’t stop. Everyone asked if I cried when the baby was born – brother, I cried before, during and after, emotions came and went. It was an amazing journey.

“I was often around children. We are Pacific Islanders, with children everywhere in our huge families. There’s a gigantic age difference between my brothers and sisters, so I’m kind of used to having kids at home.

“Having my own body is obviously a different feeling, but I’ve been waiting for it for a long time. When you have a good partner, life becomes much easier. He’s been there since day one, he knows when I’m gone I have to flip the switch to turn into a warrior. That’s why I don’t come to many fights because it’s tough for me to reconcile my gentle side with my aggression.

“She knows all about it. We’ve been together for 13 years, childhood sweetheart, it’s been a journey, brother. She was the breadwinner when I had nothing. We started from fucking scratch.

Another person who accompanied Opetai on almost every step of his journey is Tapu. However, Saturday night will be their first fight together in almost three years and their first with Opetaia as champion.

Opetaia in action during his last fight against Mairis Briedis. (Peter Wallis/Getty Images)

Having coached the first 21 fights of his son’s professional career, the couple separated. However, in this case, they are reunited and Opetaia Jr is adamant that it is worth the risk.

“There were a few things we disagreed on, a few issues,” Opetaia says of the initial breakup. “But we have moved forward and developed as people, so I felt the break was good for us. Now we are back together and moving forward, so everything is positive.

“That’s good. It’s back to basics, man. Coming back to capabilities and skills, stop trying to knock everyone’s heads off. I’m going back to what brought me here and I feel like I’ll show it in this fight.

“I’ve changed a lot since he was last in my corner, which was the fight before I won the title. They’re two completely different people, man. Entering and exiting the ring. It was fun finding that balance and it took a few weeks, but we found it and I feel like it’s going to work. That’s good.

“He’s a great boxing coach, in my opinion one of the best. I feel like it was the right move, it was astute, and I feel like everything is positive. There is always risk, there will always be change, but you have to adapt to change. I feel good and I feel this will take us to the next level.

With this, Opetaia is ready. Six years had passed since the conversation that almost ended the pursuit, but he had never looked back.

Opinions & Features

A Blackpool man is set to contest ‘No. 1 belt in the world”

Published

1 day agoon

November 22, 2024

Next month, the fight for the so-called “world No. 1 belt” will take place in Florida.

On December 6 in Pembroke Pines, Richie Leak, a 45-year-old removal specialist and father of four from Blackpool, will fight for the Police Gazette diamond belt in a bare-knuckle heavyweight fight.

The last British bare-knuckle fighter to come so close to a title shot was Jem Smith in 1887.

The Shoreditch fighter faced Jake Kilrain for the right to fight John L. Sullivan and fought for almost three hours in front of 79 spectators until it was declared a draw due to being outshone by Smith’s 74 supporters after the Londoner’s fall.

Leak is expected to have his lights out next month.

Gustavo Trujillo is the latest heavyweight to win the Police Gazette diamond belt, restored by Scott Burt, president of the Bareknuckle Boxing Hall of Fame, in 2016.

The “Cuban Assassin” – also a 6-0 (5) professional gloves boxer who lives in Miami – won all six of his bare-knuckle fights in the opening round.

“I would like to get to the second round,” said Trujillo, 31, “but they are too basic!

“There is no room in my fight plan for looking for a first-round knockout, it just happens.”

Trujillo showed off the shot selection and defense of the Cuban amateur boxer he was not.

“I wasn’t a boxer in Cuba,” he said. “I was a Greco-Roman Olympic wrestler.”

Which didn’t make him wealthy.

Trujillo left Cuba ten years ago with the intention of becoming a millionaire.

Boxing with gloves will likely make him more money than bare-knuckle boxing, but BYB Extreme keeps him busier and keeps audiences rooting for a sport in which 96 percent of fights go the distance.

Leak knows he faces a knockout next month and shrugs off the danger in the matter-of-fact way of someone who worked on doors in Blackpool as a teenager.

Leak gives the impression that no matter what Trujillo did to him, he’s had worse nights.

“I started working on doors when I was 18 because I could always argue,” he said, “but it was a terrible job.

“The local boys can’t misbehave because we’ll block them or bump into them, but the ones who come for the weekend think they can do whatever they want because they’re on the coach on Monday morning.

“They don’t care – and there are 20 buddies behind them.

“I got stabbed while I was working on a door, but luckily it hit my fat ass so there was plenty of padding!”

Leak looks very much like a Victorian boxer with a beard that earned him the nickname “The Viking.”

“It doesn’t assist me absorb the punches,” he laughed. “If I thought so, I would have grown it even longer.”

After the first round of his fight with Dan Podmore in March, his beard was stained with blood.

As is often the case in bare-knuckle boxing, Leak found the punches that turned the tide of the fight and won in the third round.

This won him the BKB heavyweight championship.

BKB has since been purchased by BYB Extreme and their champion is Trujillo.

The champions meet at the Charles F. Dodge City Center in a triangle described as the smallest fighting area in combat sports, and Trujillo is the first to defend the Police Gazette diamond belt first worn by Sullivan, the hard-living “Boston Sturdy Boy” who claimed that he inherited his strength from his Irish mother.

The belt was the invention of Richard Kyle Fox, a Dublin resident who, at the age of 29, emigrated to America in 1871.

He saved enough money to buy the struggling National Police Gazette and turned a struggling publication devoted to helping police find criminals into a colorful and controversial tabloid that gave away prizes for outlandish feats such as the longest frog jump.

Fox noticed that his readers had an appetite for sports, especially bare-knuckle boxing.

The sport was illegal in every state of America, and to counteract this, the Police Gazette reported on fights only two weeks after they took place.

Sullivan was considered America’s best fighter, and Fox supported Irishman Paddy Ryan to defeat him.

In the April 16, 1881 issue of the Police Gazette, he declared that Sullivan and Ryan would fight for “$1,000 a side, the American heavyweight championship” and “a facsimile of the belt for which Heenan and Sayers fought.”

Heenan is John C. Heenan and Sayers is Tom Sayers, the best fighters in America and England respectively.

They met near Farnborough in April 1860 and both received their belts after beating each other unconscious for two hours and 20 minutes.

The Police Gazette belt would have been in jeopardy when Ryan, Tipperary, of Troy, Modern York, and Sullivan faced each other in Mississippi City on February 7, 1882, in a 24-foot ring under London Prize Ring rules.

“Back when Sullivan was fighting, you could throw your opponent and the round would end when the knee hit the ground,” Burt said. “Some rounds lasted a few seconds, some lasted 20 minutes.”

The fighters were given 30 seconds to recover from the knockdown, and then the fight was resumed.

“Officially, Sullivan has had 51 fights,” Burt said. “If we include all the fights in bars, it will be closer to 500!

“He only fought three times bare-knuckle, against Paddy Ryan, Charley Mitchell and Jake Kilrain.

“He hated bare-knuckle boxing. You could point your eyes out and grab your hair.

“It was tedious to watch too. People left the fights. They just kept fighting until one of them gave up and they landed too many punches.

“The promoters talked to the players and told them they were afraid of breaking their arms.

“The promoters put on gloves, so they threw more punches, there were more knockouts, and it was better to watch.”

There were another 5,000 people there to see Sullivan fight Ryan, including outlaws Jesse and Frank James in drag.

They saw Sullivan drop Ryan to the jaw after 30 seconds and recalled the fight on “Memories of ’19.”vol Century Gladiator” Sullivan said the match was called off after 11 minutes because Ryan was “so disabled that the best medical care was required.”

After the fight, Fox found himself at the same bar as Sullivan and asked the waitress to invite Sullivan for a beer.

According to Burt, Sullivan replied, “No reporter is taking me away from my friends. He will have to come here.

Fox heard – as Sullivan intended – and became furious.

Burt said: “Fox wanted revenge on Sullivan and got Jake Kilrain to challenge him.

“Sullivan refused because he thought Kilrain was out of his league.

“Fox took the belt off him, put diamonds in it, called it the belt of the world and gave it to Kilrain.”

Kilrain, another Modern Yorker of Irish blood, therefore became the first holder of the Police Gazette diamond belt – until Sullivan took it from him in 1889 after a fight lasting 75 rounds – that is, two hours and 16 minutes.

This was the last world heavyweight title fight under the London Prize Ring Rules, and subsequent holders of the Police Gazette diamond belt during the glove era included Bob Fitzsimmons before the rise of The Ring magazine and the decline and eventual demise of The National Police Gazette in 1932 The belt was undisputed for over a hundred years.

Burt decided to refurbish the belt in 2016 and gifted it to Bobby Gunn, a former Canadian professional glove boxer with roots in the Irish traveling community, to “set the ball rolling in the current era.”

In 2019, Joey Beltran, a former UFC fighter from California nicknamed the “Mexecutioner,” became the first heavyweight to capture the Police Gazette diamond belt in a bare-knuckle heavyweight fight since Sullivan defeated Chase Sherman 130 years earlier in over five innings in Mississippi.

AJ Adams and now Trujillo have won the belt.

Burt said: “It was the first belt passed from champion to champion.

“There were other belts that were put up for battle after the match was over, but in the case of the Police Gazette diamond belt, you had to defeat the champion to win the belt.

“It’s the No. 1 belt in the world. There is no other belt like this. The history of no other belt comes close.”

Opinions & Features

Robbie Davies Jr is chasing constant huge fights and huge paydays

Published

2 days agoon

November 21, 2024

ROBBIE DAVIES JR didn’t want to be a stepping stone for some up-and-coming prospect. If his career started down this path, he would retire.

After a memorable defeat to Sergei Lipinet in May, which was the fifth defeat of his career, no one would be surprised if the colorful Scouser finished this match. But his display and resilience were so great that the 35-year-old still sees the airy of day and the potential for more huge fights.

On November 1, Davies will be in Belfast, specifically at the SSE Odyssey Arena, to fight Dominican Javier Fortuna in the super lightweight division on the Pro Box card. The 34-year-old’s career looks similar to Davies’s, and his fifth defeat may mean the end of “El Abejon”.

“They gave me some local names, like the odd Irish baby and the odd British baby. I don’t want to mention any names, but they didn’t excite me at all,” Davies said Boxing news.

“If I’m going to fight, I like to fight names that are at a certain level. And Fortuna was with some of the best, such as: [Joseph] Diaz and Ryan Garcia. If you go through his list, there are tons of players. He’s a very technical, solid player and I’m looking forward to it.”

Davies is at a point where his reasons for continuing to box are different from those of years ago. The victories still matter and the ambition never wanes, but these days it’s more about the love of the sport. Now in its 12th yearvol year on the track, Davies experienced good and bad moments in his 28 fights.

A recent career outside of sports is on the horizon. For now, though, he’ll keep punching as long as the huge fights last.

“I know what’s going to happen next if I beat this guy,” the maverick fighter said.

“It’s a constant fight for a huge fight, a huge fight, a huge fight. I couldn’t even say I was doing it because if I came to it [big fight]I’ll get a huge payday and I’ll just do it. I just love it.”

When asked who will be next, Davies wouldn’t reveal, but it’s definitely a fight and a fighter that excites him and keeps his career on the pulse. But before that…

“I’m going to airy this guy up [Fortuna]I’m not having fun.”

Lipinets vs. spectacle Davies could be repeated if the Liverpudlians have their way. In addition to not wanting to be used to benefit someone else’s career, he also doesn’t want to spend 10 or 12 rounds chasing his opponent around the ring.

“I just can’t be bothered,” Davies said. “But if you want to mix it up, that’s my type of fight.

“I feel like I will have a huge advantage in this fight. I know that anyone I can hit, I can hit. I showed that in my last fight Lipinets was injured many times.

I think in all my other fights I’m always the same, so depending on how he takes it and how he recovers, it will be [put] at him. But I’m going to spend the full 10 rounds there and I’m definitely going to strive for that.

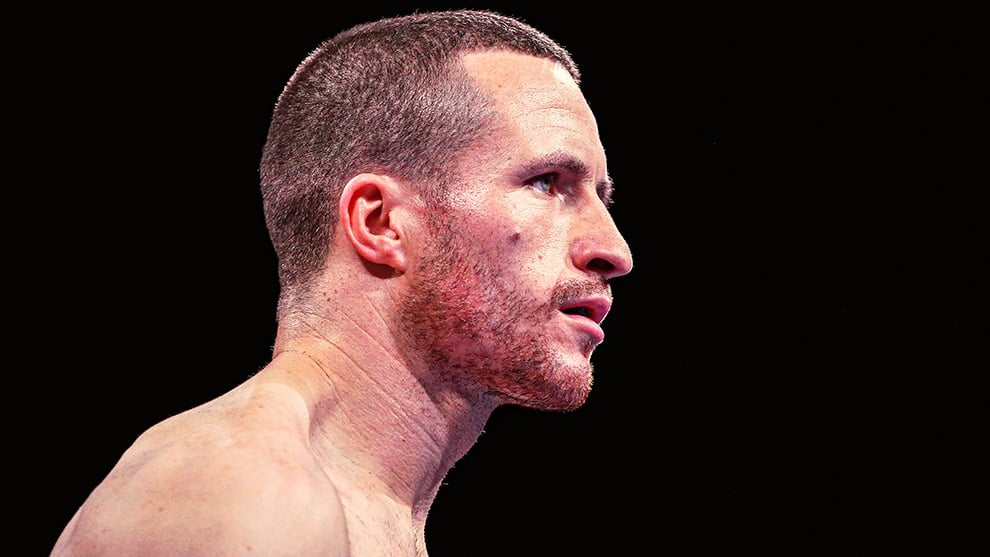

Davies Jr is a former British, Commonwealth and European super lightweight champion. (Photo: Alex Livesey/Getty Images)

Davies is still pushing for a life outside of boxing. Initially, he thought he would stay in sports or take up personal training, but after his mother’s suggestion, he was presented with an unlikely alternative. She initially helped at the local food bank and told her son that there weren’t enough adolescent workers in the area, and he eventually fell into this trap.

“I work a lot with neglected children,” he said.

“I have been running courses for years [and] I work with Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills) and ensure that children are treated well, whether the result of neglect or abuse. I started this because I was doing it part time at a local youth club. Kids now ask me to go and watch school football games and stuff like that. And then their fathers say to the children: Did you know he is a boxer? From there it escalates.

“At first, I did it voluntarily, because my mother had something to do with this place, and I was just helping her, and that’s how it started. The people who worked there, without blowing my own horn, said, “You’re great with kids. Would you never think of doing this? And then I started looking into it, but of course there were a lot of qualifications required to work with children, and being in boxing, I had a lot of free time for so many years.

“I know that when I work with kids, I know when I can assist them or just do that 1% of that [it] can do something better for them. It’s also rewarding.”

But Davies’ competitive spirit never fades, even when he’s playing soccer with his kids.

“I’m like Ronaldo against a 10-year-old and I’ll skin them all,” he said with a laugh.

In every area of life, having something to fall back on is extremely crucial. Shoot for the stars, but make sure there is something there to land on if you miss your target. Davies has won British and European super lightweight titles, and now he mixes it up with former challengers and world champions.

He has already started GNVQ Level 4 in Children’s Social Care, which can take up to two years to complete. Working with younger people who had experienced complex situations in their lives opened Davies’ eyes beyond what he had seen in boxing.

“There is no end to what you can do to assist children,” he said.

“You don’t realize how much some people struggle until you’re actually there.

“It’s a gloomy thing. No matter how much you can do, you will never assist or repair the trauma, but you can assist the 1%. This gives you satisfaction while working. Plus, with the time I need and how much I have to do, I can obviously still do boxing, which I still love, so it’s a good balance of what I have at the moment.”

Davies is full of energy, whether you talk to him on the phone or in person. It’s straightforward to see why working in children’s social care would be a good fit for someone of his character and personality. However, a few years ago his life took a different direction when his desire to run marathons won.

After injuring his leg during the fight with Darragh Foley in March 2023, which ended with the Irishman winning by TKO in the third round, Davies needed time to regenerate. He predicted he would be back on the road three months later, but doctors thought otherwise.

Bored Robbie Davies clearly needs extreme medication and completed his first marathon in August.

“I signed up for my first marathon two and a half weeks in advance, obviously not knowing what it would take to run a marathon,” he recalled. “I ran the Chester Marathon and my body just fell apart.

“I had 60- and 70-year-olds running away, tapping me on the shoulder and saying, come on, adolescent man, you can keep going. And I say I’m fucking dying here,” he laughed.

“From that point on, I thought I’d get right into it, and then I ran Up-to-date Year’s Eve, Up-to-date Year’s Day and back-to-back marathons. Then I went from Manchester to Liverpool, 50 miles, ultramarathon. Then I did London, I’ve done some now.

Looking back on his career, Davies doesn’t think he’s achieved any success, but he feels inside he could have done better. A conversation that led him to briefly sing “Ooh La La” by The Faces, which includes the line, “I wish I knew what I know now…”.

“I remember when I was younger I went on a men’s holiday every year and no other player did it,” Davies said.

“They were solid, focused in the box. I probably enjoyed life. And then when I turned pro and started focusing more on zones, I was winning titles and stuff like that.

“If my career ended now, I’d probably say I’m ecstatic, but I’ll always be haunted by the thoughts that I would have done this and I should have done that. But I think a lot of players do that.”

“I was knocked out by Oleksandr Usyk – here’s how Tyson Fury can beat him” – EXCLUSIVE

CHRIS EUBANK JR CANDIDLY ADMITS, ‘If I lose to Conor Benn, I’M FINISHED!’

Liam Smith vs Chris Eubank Jr 2 Review | #29

Trending

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoMax Holloway is on a mission at UFC 212

-

Interviews1 month ago

Interviews1 month agoCarl Froch predicts that Artur Beterbiev vs Dmitry Bivol

-

Interviews1 month ago

Interviews1 month agoArtur Beterbiev vs Dmitry Bivol

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoCris Cyborg ready to add a UFC title to her collection

-

MMA6 months ago

MMA6 months agoThe Irish showed up in droves at the Mayweather-McGregor weigh-in

-

Boxing4 months ago

Boxing4 months agoLucas Bahdi ready to test his skills against Ashton Sylve

-

Interviews6 months ago

Interviews6 months agoI fell in love with boxing again

-

Opinions & Features2 months ago

Opinions & Features2 months agoDmitry Bivol: The story so far

The Real Person!

Author holloporn.win/v/6495013.html acts as a real person and passed all tests against spambots. Anti-Spam by CleanTalk.

October 1, 2024 at 8:10 am

I havve been surfing online more than 3 hours today, yet I never found anyy interesting artixle luke yours.

It’s pretty worth enough ffor me. Personally, if alll site owaners and blggers made good content ass youu did,

thhe internet will bee a lot mire ussful thasn ever before.